Forget the majestic, sky-scraping giants you typically picture. The future of wind power, particularly in bustling urban landscapes, increasingly hinges on mastering VAWT design, aerodynamics, and efficiency. These aren't just technical buzzwords; they're the critical levers that empower Vertical Axis Wind Turbines (VAWTs) to quietly, effectively, and resiliently convert even the most capricious urban breezes into clean energy. Understanding these elements unlocks their true potential, moving them from niche curiosities to essential components of a decentralized, sustainable energy grid.

At a Glance: What You'll Learn About Next-Gen VAWTs

- VAWTs excel in complex winds: Unlike their horizontal counterparts, VAWTs thrive in turbulent, omnidirectional airflow common in cities.

- Design is everything: Blade shape, number of blades, and rotor size dramatically impact performance.

- Aerodynamics is nuanced: It's not just about catching wind; it's about managing lift, drag, and dynamic stall.

- Efficiency metrics matter: Look beyond power output to understand Coefficient of Power (Cp), Tip Speed Ratio (TSR), and starting torque.

- Urban integration is key: VAWTs offer unique advantages for seamless blending into built environments.

- Innovation is constant: Researchers are continually addressing challenges like self-starting and vibration through smart materials and adaptive controls.

The City's Silent Powerhouse: Why VAWTs Matter Here

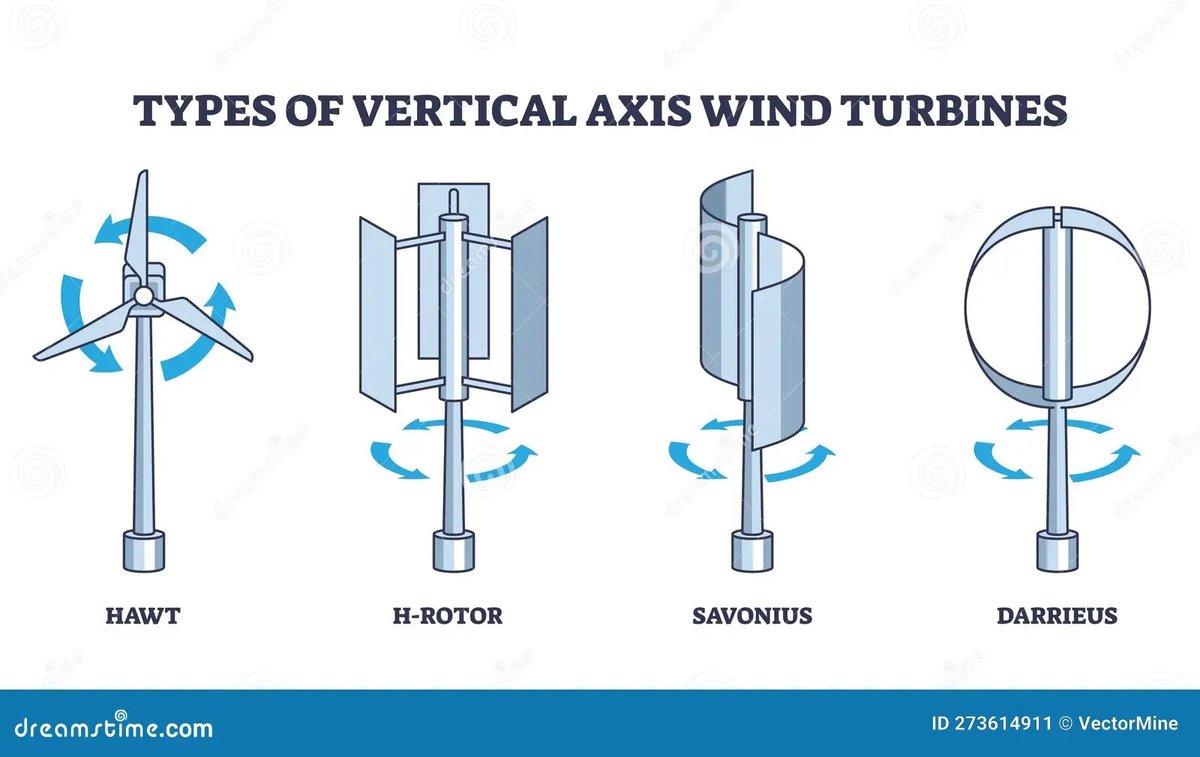

When you think "wind turbine," a towering structure with massive propeller blades likely comes to mind. These Horizontal Axis Wind Turbines (HAWTs) are optimized for consistent, high-speed winds found in open fields or offshore. But cities? They're a different beast. Buildings create wind tunnels, eddies, and unpredictable gusts that make traditional HAWTs less effective and often impractical.

This is precisely where VAWTs shine. Their inherent ability to capture wind from any direction without reorientation makes them ideal for environments where wind direction shifts constantly. They're often quieter, have a smaller visual footprint, and can be mounted closer to the ground, even on rooftops. This adaptability positions VAWTs as a crucial piece of the puzzle for urban renewable energy, reducing reliance on long transmission lines and bolstering local energy resilience. But harnessing this potential requires deep dives into their intricate design and aerodynamic principles.

The Aerodynamic Dance: How VAWTs Translate Wind into Power

At its heart, a wind turbine is an energy converter, turning kinetic energy from wind into mechanical energy, then electricity. For VAWTs, this conversion is a fascinating interplay of forces.

Lift-Driven vs. Drag-Driven: Two Paths to Rotation

Generally, VAWTs fall into two main categories based on their primary operating principle:

- Drag-Driven VAWTs (e.g., Savonius Turbines):

- These turbines operate much like an anemometer, where the wind pushes against concave surfaces, creating a pressure differential that causes rotation.

- Pros: Excellent self-starting capability, high starting torque (good for pumping or direct mechanical drive), simple design, often very robust.

- Cons: Lower aerodynamic efficiency compared to lift-driven designs, as the drag force on the returning blade can impede rotation.

- Visual: Imagine two halves of a barrel split vertically and offset, forming an S-shape.

- Lift-Driven VAWTs (e.g., Darrieus, H-Rotor Turbines):

- These designs utilize airfoils (like airplane wings) that generate lift as wind flows over them. The difference in pressure across the airfoil creates a force perpendicular to the wind flow, driving rotation.

- Pros: Higher aerodynamic efficiency, capable of achieving higher rotational speeds and power output.

- Cons: Typically poor self-starting capabilities (they often need a nudge or a motor to get going), can experience dynamic stall.

- Visual: The classic "egg-beater" shape (Darrieus) or vertical straight blades (H-Rotor).

The choice between lift and drag is fundamental to the vertical axis wind power generator's overall performance characteristics. For most electrical generation applications, lift-driven designs are preferred due to their higher efficiency potential, despite their self-starting hurdles.

The Intricacies of Airflow: Beyond Simple Pushing

Understanding VAWT aerodynamics goes deeper than just lift and drag. As the blades sweep through their circular path, they experience continuously changing relative wind speeds and angles of attack. This leads to several complex phenomena:

- Dynamic Stall: A critical challenge for lift-driven VAWTs. As a blade rotates, its angle relative to the incoming wind changes. At certain points, this angle can become too steep, causing the airflow to separate from the blade surface. This results in a sudden, dramatic loss of lift and an increase in drag, severely impacting efficiency and creating unsteady forces.

- Wake Interference: As one blade passes, it creates a turbulent wake that affects the performance of subsequent blades. This interference can reduce the effective wind speed for following blades and contribute to dynamic stall.

- Turbulence Management: Urban environments are inherently turbulent. A well-designed VAWT must not just tolerate turbulence but ideally capitalize on it, maintaining stable operation and performance even in gusty, unpredictable conditions. This is where VAWTs often outperform HAWTs, which can struggle with rapidly changing wind directions.

Decoding VAWT Design: Key Elements for Peak Performance

A VAWT's physical attributes are not arbitrary; each design choice is a careful negotiation with the laws of physics, aimed at maximizing energy capture and operational stability.

Blade Profile: The Heart of the Aerodynamics

The shape of the turbine blades (the "airfoils") is paramount, particularly for lift-driven designs.

- Symmetrical vs. Asymmetrical Airfoils: Symmetrical airfoils are often used because they perform similarly regardless of the direction of relative wind, which changes continuously for a VAWT blade. However, some advanced designs experiment with asymmetrical airfoils or cambered blades to optimize for specific parts of the rotation cycle, though this can introduce complexities.

- NACA Airfoils: Standardized airfoil shapes developed by NASA (formerly NACA) are frequently adapted for VAWTs. Common choices include NACA 0012, 0015, or 0018, which offer a good balance of lift and drag characteristics. The thickness and curvature of these profiles significantly influence how effectively lift is generated and how resistant the blade is to dynamic stall.

- High Lift-to-Drag Ratio: Designers strive for airfoil shapes that produce high lift with minimal drag across a range of angles of attack, crucial for efficient power generation.

Number of Blades: A Balancing Act

While it might seem that more blades would capture more wind, it's not that simple.

- Fewer Blades (e.g., 2 or 3):

- Pros: Less material, lighter rotor, reduced wake interference between blades, potentially higher peak efficiency at optimal wind speeds.

- Cons: Can have poor self-starting characteristics, may experience greater torque ripple (fluctuations in rotational force), potentially higher tip speed ratios needed for optimal performance.

- More Blades (e.g., 4 or 5+):

- Pros: Improved self-starting capability, smoother torque output, better performance in very low wind speeds, increased solidity.

- Cons: More material, heavier rotor, increased wake interference, potentially lower peak efficiency due to aerodynamic drag penalties.

The sweet spot often lies at 3 or 4 blades for lift-driven VAWTs, offering a compromise between self-starting, smooth operation, and aerodynamic efficiency.

Rotor Diameter and Height: Scaling for Purpose

The overall dimensions of the VAWT are dictated by its intended application and the available wind resource.

- Diameter: A larger diameter sweeps a larger area, capturing more wind energy. However, it also increases structural loads and material costs. For urban settings, diameter is often constrained by available roof space or mounting points.

- Height: Taller rotors can access higher wind speeds (as wind speed generally increases with altitude). Yet, structural stability and aesthetic integration become more challenging. The aspect ratio (height-to-diameter) is a key design parameter, influencing the turbine's stability and how effectively it captures wind across varying heights.

Turbine Solidity: Density of the Rotor

Solidity refers to the ratio of the total blade area to the rotor's swept area. It's a measure of how "dense" the turbine is.

- Low Solidity (e.g., 2-3 blades with slender airfoils): Characteristic of high-speed, lift-driven VAWTs designed for efficiency at higher wind speeds.

- High Solidity (e.g., multiple blades, larger chords, Savonius designs): Often found in low-speed, high-torque turbines with better self-starting capabilities, suited for very low wind environments or applications requiring immediate power.

Matching solidity to the specific wind conditions and power requirements is crucial. An overly solid turbine in high winds might create too much drag, while an insufficiently solid one might struggle to start.

Materials Science: Lighter, Stronger, Cheaper

The materials used for blades and support structures play a massive role in performance, cost, and lifespan.

- Blades: Modern VAWT blades often utilize composites like fiberglass, carbon fiber, or reinforced plastics. These materials offer high strength-to-weight ratios, allowing for lighter rotors that can accelerate faster and experience less structural stress. Research is also exploring bio-composites and recycled materials for sustainability.

- Support Structure: Aluminum, steel, or advanced alloys are common for the central shaft and support arms, chosen for their stiffness, strength, and corrosion resistance. Reducing the weight of these components lowers overall turbine mass, improving efficiency and simplifying installation.

Efficiency Unpacked: Metrics That Matter for VAWTs

When evaluating a VAWT, simply looking at its "kilowatt rating" only tells part of the story. Understanding the underlying efficiency metrics reveals how well it truly performs across a range of conditions.

Coefficient of Power (Cp): The Gold Standard

The Coefficient of Power (Cp) is the most critical metric for any wind turbine. It represents the ratio of the power extracted by the turbine to the total power available in the wind. In simpler terms, it tells you how much of the wind's energy the turbine can actually convert into useful work.

- Betz Limit: No wind turbine, regardless of design, can extract more than 59.3% of the kinetic energy from the wind. This theoretical maximum is known as the Betz Limit.

- Typical VAWT Cp: While VAWTs generally have lower peak Cp values than their HAWT counterparts (often in the range of 0.30 to 0.40 compared to 0.45-0.50 for HAWTs), their ability to perform well in turbulent, omnidirectional winds gives them an advantage in certain applications where HAWTs would struggle or fail to operate.

Tip Speed Ratio (TSR): Speeding Up for Power

The Tip Speed Ratio (TSR) is the ratio of the speed of the blade tips to the speed of the incoming wind. It's a dimensionless number that indicates how fast the rotor is spinning relative to the wind.

- Low TSR (e.g., 1-3): Typical for drag-driven VAWTs like Savonius, which are robust and have good starting torque but generate less power.

- High TSR (e.g., 3-6+): Characteristic of lift-driven VAWTs like Darrieus and H-Rotors. Higher TSR generally correlates with higher efficiency for lift-driven designs, as the blades encounter the wind at more optimal angles of attack.

- Optimizing TSR: Each VAWT design has an optimal TSR at which it achieves its maximum Cp. Designers aim to operate the turbine as close to this optimal TSR as possible across various wind speeds, often using sophisticated control systems.

Starting Torque: Getting the VAWT Moving

Starting torque is the amount of rotational force a turbine can generate at zero or very low rotational speed to overcome static friction and begin spinning.

- The VAWT Challenge: Many efficient lift-driven VAWTs struggle with self-starting. At very low wind speeds, the lift forces generated aren't sufficient to overcome the inertia and friction of the rotor. This is a significant practical hurdle, especially for off-grid applications where continuous operation is desired.

- Design Solutions:

- Hybrid Designs: Combining drag-driven elements (like a small Savonius section) with lift-driven blades to provide the initial torque.

- Augmented Aerodynamics: Specific blade profiles or add-ons that enhance starting torque.

- Electronic Control: Using a small motor to "kick-start" the turbine, then letting the wind take over.

- Higher Solidity: As mentioned, more blades can help with self-starting.

Low Wind Speed Performance: The Urban Imperative

For urban environments, the ability of a VAWT to generate power effectively at low wind speeds (e.g., 3-7 m/s) is more important than its peak output at gale-force winds. Cities rarely experience consistently high winds, but they do have frequent, moderate breezes. A turbine that can "cut in" (begin producing power) at very low speeds and maintain a decent Cp in that range will be far more productive in an urban setting than one designed solely for high-speed efficiency.

Challenges and Innovations: Pushing VAWT Boundaries

Despite their unique advantages, VAWTs still face specific challenges that researchers and engineers are actively addressing, leading to exciting innovations.

Dynamic Stall Mitigation: Smoother Sailing

Dynamic stall remains a major hurdle for high-performance VAWTs, causing efficiency drops and structural fatigue.

- Passive Solutions: Optimizing airfoil shapes, varying blade chord (width) along the blade's height, or incorporating vortex generators (small fins that re-energize the boundary layer) to delay flow separation.

- Active Solutions: Advanced designs explore active pitch control, where individual blade angles are adjusted dynamically during rotation to optimize angle of attack and prevent stall. This is complex but offers significant performance gains.

- Flexible Blades: Some concepts involve blades made of flexible materials that can deform slightly under wind load, passively adjusting their shape to mitigate stall and absorb gusts.

Self-Starting Issues: Overcoming Inertia

Beyond hybrid designs, innovations are focusing on more elegant solutions:

- Variable Geometry Blades: Blades that can change their profile or angle specifically during startup to maximize torque, then revert to an efficient shape once running.

- Savonius-Darrieus Hybrids: Explicitly integrating a smaller Savonius rotor within or alongside a Darrieus rotor to provide reliable self-starting torque.

- Rotor Augmentation: Using shrouds or diffusers around the rotor to accelerate wind flow and improve initial torque.

Noise and Vibration: The Neighborly Concern

One of VAWTs' selling points is often lower noise compared to HAWTs. However, poorly designed VAWTs can still generate unwanted noise and vibration, especially when mounted on buildings.

- Aerodynamic Noise: Caused by turbulent airflow over the blades. Smooth blade finishes and optimized airfoils can reduce this.

- Mechanical Noise: From bearings, gears, or generator. High-quality components and proper maintenance are essential.

- Vibration Mitigation: Structural damping, careful mounting strategies, and active control systems can minimize vibrations transferred to buildings, ensuring a peaceful coexistence with urban dwellers.

Smart Controls and Adaptive Blades: The Future is Responsive

The advent of microprocessors and advanced sensor technology is transforming VAWT capabilities.

- Real-time Optimization: Control systems can monitor wind conditions, rotor speed, and blade stresses, then adjust generator loading or (in active designs) blade angles in real time to maintain optimal TSR and maximize power output.

- Gust Management: Smart controls can detect sudden gusts and momentarily reduce generator load to prevent over-speeding or excessive stress, enhancing durability.

- Predictive Maintenance: Integrating sensors that monitor vibration, temperature, and performance allows for early detection of potential issues, moving from reactive to predictive maintenance.

Vertical Integration with Buildings: Architecture Meets Energy

The ultimate urban VAWT isn't just on a building, but part of it.

- Building-Integrated Wind Turbines (BIWTs): Designs that are structurally integrated into building facades or rooftops, not just bolted on. This can leverage the building's form to channel and accelerate wind, creating "urban wind farms."

- Aesthetic Harmony: Future designs will prioritize not just performance but also visual appeal, blending seamlessly with architectural aesthetics rather than being an afterthought.

Real-World Considerations: Siting, Installation, and Maintenance

Theoretical design prowess must translate into practical, reliable operation. Deploying VAWTs effectively requires careful attention to siting, installation, and ongoing care.

Wind Resource Assessment: Micro-Siting is Macro-Critical

Unlike open fields, urban wind environments are notoriously complex.

- Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD): Sophisticated computer simulations are increasingly used to model airflow around buildings and predict local wind speeds and turbulence patterns. This "micro-siting" is crucial for identifying optimal locations on a rooftop or within an urban canyon.

- Anemometer Studies: While CFD provides valuable insights, direct measurement with anemometers (wind speed sensors) over an extended period at the proposed site is still the gold standard for verifying predictions and understanding site-specific wind characteristics.

- Obstruction Awareness: Buildings, trees, and other structures create wakes and turbulence. Positioning VAWTs above the turbulent boundary layer created by surrounding obstacles is critical for consistent performance.

Grid Integration vs. Off-Grid Solutions: Powering What Matters

How the VAWT connects to the power system defines its role.

- Grid-Tied Systems: Most modern VAWTs are designed to feed electricity directly into the local power grid, often with net-metering agreements that allow users to sell excess power back. This requires an inverter to convert the turbine's AC output to grid-compatible AC and safety features to disconnect during power outages.

- Off-Grid Systems: For remote cabins, telecommunications towers, or street lighting, VAWTs can charge battery banks. This setup requires charge controllers to manage battery health and often a smaller inverter for AC loads. The VAWT's low-wind performance and robust starting torque are particularly valuable here.

- Hybrid Systems: Combining VAWTs with solar PV, energy storage, or even diesel generators for maximum reliability and energy independence. This multi-source approach leverages the strengths of each technology.

Durability and Lifespan: A Long-Term Investment

A VAWT represents a significant investment, and its longevity is key to its economic viability.

- Robust Materials: As discussed, high-quality, weather-resistant composites and metals are crucial.

- Bearing Systems: The main bearings, which support the rotor, are critical components. They must be robust, properly sealed, and require minimal maintenance. Magnetic levitation bearings, though costly, offer friction-free operation and extended lifespans.

- Corrosion Protection: Especially important in coastal or industrial environments where salt spray or pollutants can accelerate material degradation.

- Lightning Protection: For any outdoor structure, proper grounding and lightning arrestors are essential.

Choosing the Right VAWT: A Decision Framework

Selecting the ideal VAWT involves aligning its design characteristics with your specific needs and environment.

Small-Scale Residential: Powering Homes and Gardens

- Priorities: Low noise, compact footprint, aesthetic appeal, good low-wind performance, reliable self-starting.

- Common Types: Smaller H-Rotor Darrieus or Savonius-Darrieus hybrids. Often grid-tied with battery backup options.

- Considerations: Local zoning regulations, potential for micro-siting on rooftops or in yards, visual impact on neighbors.

Urban Commercial: Rooftop Resilience and Brand Image

- Priorities: Higher power output, sophisticated control systems, durability, seamless integration with building architecture, low vibration.

- Common Types: Larger H-Rotor or multi-blade Darrieus arrays, often custom-designed for the building.

- Considerations: Structural load capacity of the building, maintenance access, integration with building management systems, marketing value as a sustainability statement.

Hybrid Systems: Maximizing Reliability

- Priorities: Complementary power generation (e.g., wind at night, solar during day), robust energy storage, intelligent energy management.

- Common Types: Any VAWT paired with solar PV, battery banks, or other generators.

- Considerations: System integration complexity, overall capital cost, optimizing the balance between different energy sources for specific load profiles.

The Road Ahead: VAWTs in a Sustainable Future

The journey of VAWTs from conceptual designs to viable, urban-friendly energy solutions is an exciting one, driven by continuous advancements in design, aerodynamics, and efficiency. We're seeing a maturation of the technology, moving beyond the initial skepticism to a place where VAWTs are recognized as a vital, complementary player in the global energy transition.

The future will likely bring more aesthetically integrated designs, smarter control systems that can adapt to changing urban microclimates, and more robust materials that push the boundaries of durability and cost-effectiveness. As urban populations grow and the imperative for localized, renewable energy intensifies, mastering the intricacies of VAWT design, aerodynamics, and efficiency won't just be an academic pursuit; it will be a cornerstone of how we power our cities, quietly and sustainably, for generations to come.